Carlotta Cardana (Verbania, IT 1981) is an Italian portrait and documentary photographer based in London.

After obtaining a degree in Fine Arts and a photography diploma, she lived in Argentina and Mexico City, where she started freelancing as an editorial photographer. Her recent personal work investigates how communities are affected by economic upheaval and oppression. She is also interested in how social contexts affect personal identities, such as amongst minorities or subcultures. The Fourth Freedom (2011-12) questioned the role of national and regional identity among young Italians living in Europe. Modern Couples (2012-14) explored not only how members of a subculture use their appearance to construct their identity and to express their values and beliefs, but also how two individuals in a relationship tend to form an identity that encompasses both. The Red Road Project (2013- ), an on-going collaboration with Lakota writer Danielle SeeWalker, explores the relationship between Native American peoples and their identity today, while aiming to highlight inspiring stories from tribal people.

Her work has been awarded and exhibited in festivals and galleries across Europe and the U.S. – among others FOTOGRAFIA – Festival Internazionale di Roma, Noorderlicht Photofestival, Month of Photography Los Angeles, Kolga Tbilisi Photo, ImageSingulières, Sete – and publications such as The Guardian Weekend, The New York Times T Magazine, De Volkskrant, Marie Claire, L’OBS.

Danielle SeeWalker (born in North Dakota, 1983) is a Hunkpapa Lakota artist, activist and mother of two based in Denver, Colorado. She is also the second half and writer of The Red Road Project. Danielle is an enrolled member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe in North Dakota where she was born and raised and descends from the Hunkpapa Lakota chief, Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake (Sitting Bull).

Because of the historical stigma often associated with being Native American (particularly in North Dakota where she grew up), Danielle was ashamed to identify as American Indian as a young girl. That experience has fueled her passion and dedication to this project with hopes to inspire Native American youth and the Native communities in general. Today, Danielle studies and lectures on Native American culture in the 21st century and how historical and contemporary American Indian issues play a part.

Danielle has a background in sociology, anthropology, psychology and Native American studies at Albright College (BS) and Kutztown University (MA).

About ‘THE RED ROAD PROJECT‘:

“What did we do so wrong that they would want to wipe us out? Strip us of our land, force us onto reservations, take our language and clothing, make our children go into boarding schools and punish them for crying for their mothers. We cared for this land and now look at it. Look at us; we are dying. We were a people of millions and now some tribes have a few left, if any. Some have died out all together. We are losing our languages, many of our lives have succumbed to alcohol, our children don’t know our traditions. We never took gold, we have no interest in oil, we only cared for the land and that is all we know. We ask ourselves everyday, what did we do so wrong?” – James Shot With Two Arrows, Medicine Man (2013)

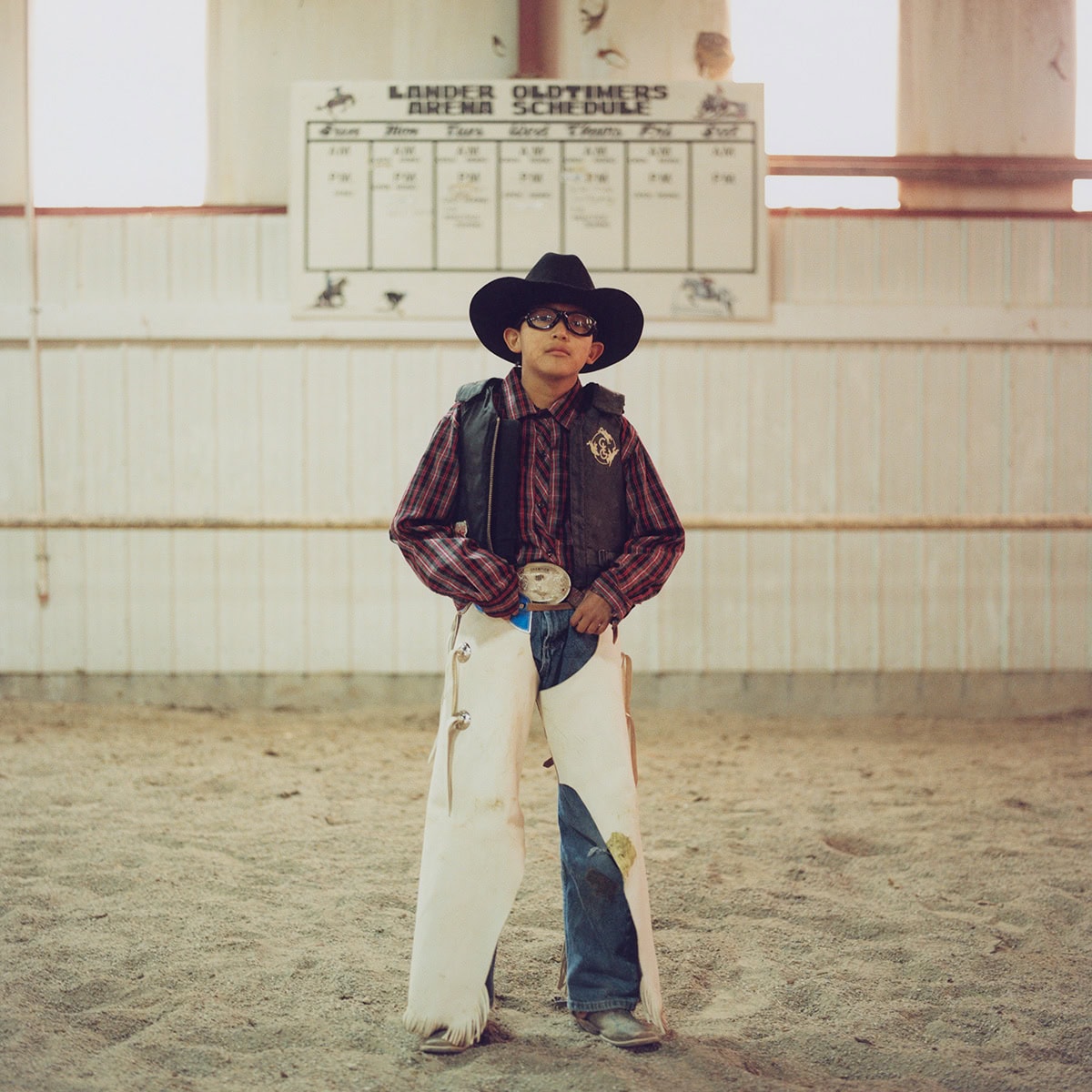

Since inception, The Red Road Project’s purpose is to explore the relationship between traditional Native American culture and the identity of tribal people today. For more than a century, the culture and people have survived some of the most horrific events in American history, including cultural genocide. Contrast to these events, the resilience of the people is utmost inspiring and the aim is to highlight these stories. The title of this work comes from various Native American teachings that encourage one to follow “the red road”. One will often hear Native Americans say they are walking “the red road” which identifies them as being on the path to positive change. With this work, we want to illustrate how Native American culture has had to overcome cultural genocide and highlight not only the backlash of the struggles but bring forth the strength, sovereignty, and pride among these people.

The clash of European colonization and the indigenous people of North America began in the 15th century, but it wasn’t until the late 19th century did Native Americans face a whole new set of challenges. The “boarding school era” began in the late 1800’s and was designed to assimilate Native Americans into Euro-American culture while offering a basic education and acquired skills. It was not understood at the time just how much this era would leave deep, residual scars that still heavily exist among Native American people today. The motto of the boarding schools was, “kill the Indian, but save the man.” Native children were taken from their families, forced to cut their hair, speak only English and were severely punished if they practiced any of their traditions or spoke their Native tongue. As the “board school era” was coming to a close in 1970’s, there were still thousands of indigenous children enrolled in these schools. Generations of Natives that have passed through boarding schools were left dealing with immense traumas of abuse, neglect and separation from family and culture. This led to high rates of suicide, substance and alcohol abuse, sexual abuse and violence, and other health disparities such as high blood pressure and diabetes. Danielle SeeWalker, the writer on this project, understands firsthand how the aftermath of boarding schools has affected Native American people today. Danielle’s grandmother was a boarding school child and was the last generation in her family to speak their Lakota language fluently. She never fully recovered from the trauma that boarding school caused her and didn’t know how to cope except by turning to alcohol. Alcoholism eventually took over and she lost custody of all her children to the foster system. The cycle of alcohol abuse continues with today’s generation and many of her family members have passed away prematurely and never fully re-embraced their cultural identity. With all odds stacked against her, Danielle has made a conscious decision to break that cycle and focus on walking “the red road” and re-ignite her cultural identity within herself and her children.

Although many cultural practices were halted for several decades due to the effects of boarding schools, Native Americans’ never lost sight of their strong connection with “unci maka” (grandmother earth) and that is evident in many of the photographs in this project. Linda Black Elk, an ethnobotanist living on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, says it best: “We don’t just live here; we participate with the earth, plants and animals. They take care of us and we take care of them.” This connection with the land is the foundation to so many other things in Native American cultures including ceremonies, oral stories, traditional arts and even language. Reclamation of original homelands, language revival, taking back ownership of ceremonies, and raising confident children are all examples of the successful milestones that Native Americans have achieved during the long, uphill battle to self-identity in the 21st century.